29 April 2020

The Pre-antibiotic Age – forgotten knowledge coming back in to light…

British pioneering scientists Downes and Blunt demonstrated how sunlight could kill and inhibit the development of the – at this time in 1877 – newly discovered bacteria. By placing bacteria in different environments, respectively in direct sunlight, indirect sunlight and darkness. Downes and Blunt observed, through new and improved microscopes, how the bacteria only thrived, deprived of the direct and energetic, ultraviolet light. Like in today´s clinical trials, they worked with intervention and control groups.

In one of their experiments (1) they affixed four sealed glass tubes with Pasteur’s solution (a solution consisting of sugar, water and ammonia) in a SE-facing window exposed to direct sunlight during a summer. In the control group, they placed four identically sealed glass tubes with the same solution, but protected from the sunlight, completely covered by thin sheets of lead. One month later only the covered glass tubes showed full bacterial growth, while none of the glass tubes, exposed to the UV light showed any signs of bacteria. In this way, Downes and Blunt scientifically demonstrated that sunlight works as an antiseptic agent on bacteria, also through clear laboratory glassware.

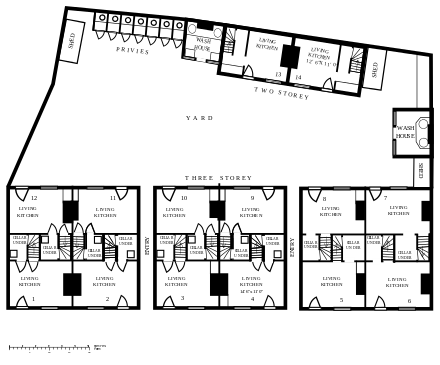

The UV pioneers Downes and Blunt and their discoveries of the effects of light on bacteria subsequent played a central role, not only in the treatment of several diseases but in architectural planning and later in Modernism. The first scientific evidence of these positive effects of sunlight in the treatment of diseases arrived only a few years later. The Danish doctor Niels R Finsen pioneered both heliotherapy (sunlight therapy) and actinotherapy (artificial lighting enriched by short waved near-ultraviolet “chemical” light e.g. the Finsen Lamp) in the fight against a disease caused by bacteria, lupus vulgaris also called skin tuberculosis. In this period, daylight not only was an agent in the treatment of diseases, it also served as a prophylactic agent in the protection from diseases (2). In an Era where light, air and openness replaced the dark and poorly ventilated back-to-back-houses deprived of direct access to sunlight, in often densely populated urban areas and cities.

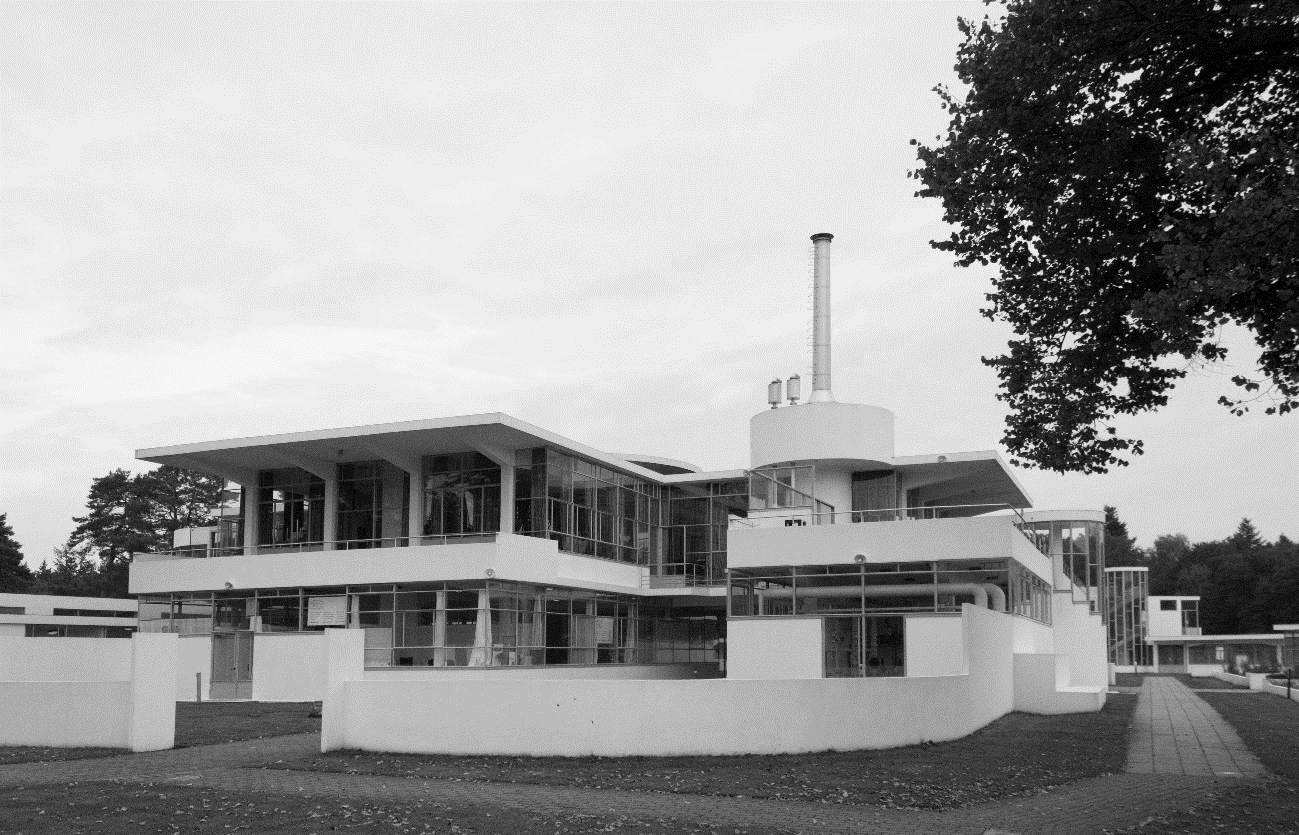

Architectural planner Ebenezer Howard came up with more radical, architectural suggestions in the efforts to fight the dark and polluted urban areas and the growing densification of the urban life. Ebenezers publication “Garden Cities of Tomorrow” (3) provided a masterplan for a better balance between urban life, and access to sunlight, fresh air and natural surroundings. His efforts resulted in the so-called Garden City Movement, with Letchworth as a prominent architectural example, becoming an emblem of the pre-antibiotic architectural urban planning. Like the sanatoria and the hospitals, the Garden City Movement focused on sunlight, fresh air and natural surroundings as important architectural elements in the fight against infectious diseases – at least as long as the medical sciences couldn’t protect against the diseases.

However, the Garden City Movement never succeeded in changing the urban densification. Medical advances, including the discovery of penicillin and vaccines (4) against tuberculosis, changed the role of the architecture – and the architecture itself – significantly in the period to come, making this pre-antibiotic architectural planning redundant. For many of us the rest is history: During a new era of medical advancement, the physical surroundings – including the architecture – lost its affinity to health, a relation, which otherwise had been strong and inseparable through historical time. Architects with medical knowledge, and doctors with architectural knowledge became rarer. Doctors no longer involved themselves in the construction of schools and hospitals to the same extent as before. It is noteworthy that medicine, and particularly the development of various vaccines, manifest themselves so clearly in the architecture. This shows the close relationship between architecture and medicine (5), which manifests itself in the very absence of a healthy architecture, as better and more effective medications became widespread in The Postwar Period, from 1945 and up to the present day. The architecture today no longer offering the same framework for fresh air, or for that matter natural light, as it did before. In the following decades the medical treatment, resulted in the technological hospitals moving into the center of the cities – in the same densely populated areas, and in the same lack of light and fresh air – which the sanatoriums fled from originally.

Classical typologies were replaced by more compact building shapes, which did not utilize the sunlight as well, reducing the actual number of sunshine-hours inside the building during the day and during the year. At the same time, deeper building-plans with lower ceiling heights were implemented. Instead of previously recommended ceiling-heights of 14 feet – equivalent to approx. 4.25 m – the ceiling heights were lowered to the current 2.7 m. Increased glass areas could not compensate for the reduced ceiling heights and the increased depths of the buildings. Building typologies also became taller and more compact, letting in less daylight and less fresh air; the preventive and healing elements of the pre-antibiotic architecture were forgotten… again, the rest is history. That is until today´s emergence of multi resistant bacteria outbreaks and last but not least today´s COVID-19 corona virus.

While light of the sun in the pre-antibiotic era was considered the first line of defense against bacteria, antibiotics such as vancomycin etc, is first line treatment in the fight against the infections that constitute a major problem today. Hospital infections, which not only amount to great expenses in terms of more bed days and hospital acquired infections (6, 7, 8), but also represent a real health threat. In Denmark it is estimated that around 8-10% of all bed days are caused by hospital infections, corresponding to approx. 400,000 bed days (9) per year in Denmark. Several factors suggest that the era of antibiotics may be over. According to the WHO (10), we are facing a global crisis in antibiotics, looking at an increasing number of multi-resistant bacteria, while we, unfortunately, see fewer, new medical responses, in the form of effective vaccines against these bacteria and viruses. In this context, the current 2020 COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic is a good reason to restore the significance of architecture and reestablish light and the physical environment as factors important to the overall health and to the prevention of diseases.

In this reestablishing, we may see many good advices on what to do. In this process however, two steps forward may be two steps back, and l suggest not only to establish new ways of planning, but also to reestablish parts of the earlier architectural planning of daylight and fresh-air of pre-antibiotic age and reconsider some of today´s post-antibiotic best practices in architectural planning. Here a couple of general suggestions on how to start this process.

- It has even come so far that a doctor last year in earnest came with a proposal that there should be airtight houses with thick glass walls where the air would come in through small vents with filter appliances… Airtight buildings without openable windows and natural cross ventilation may be problematic when it comes to infectious diseases and virus…

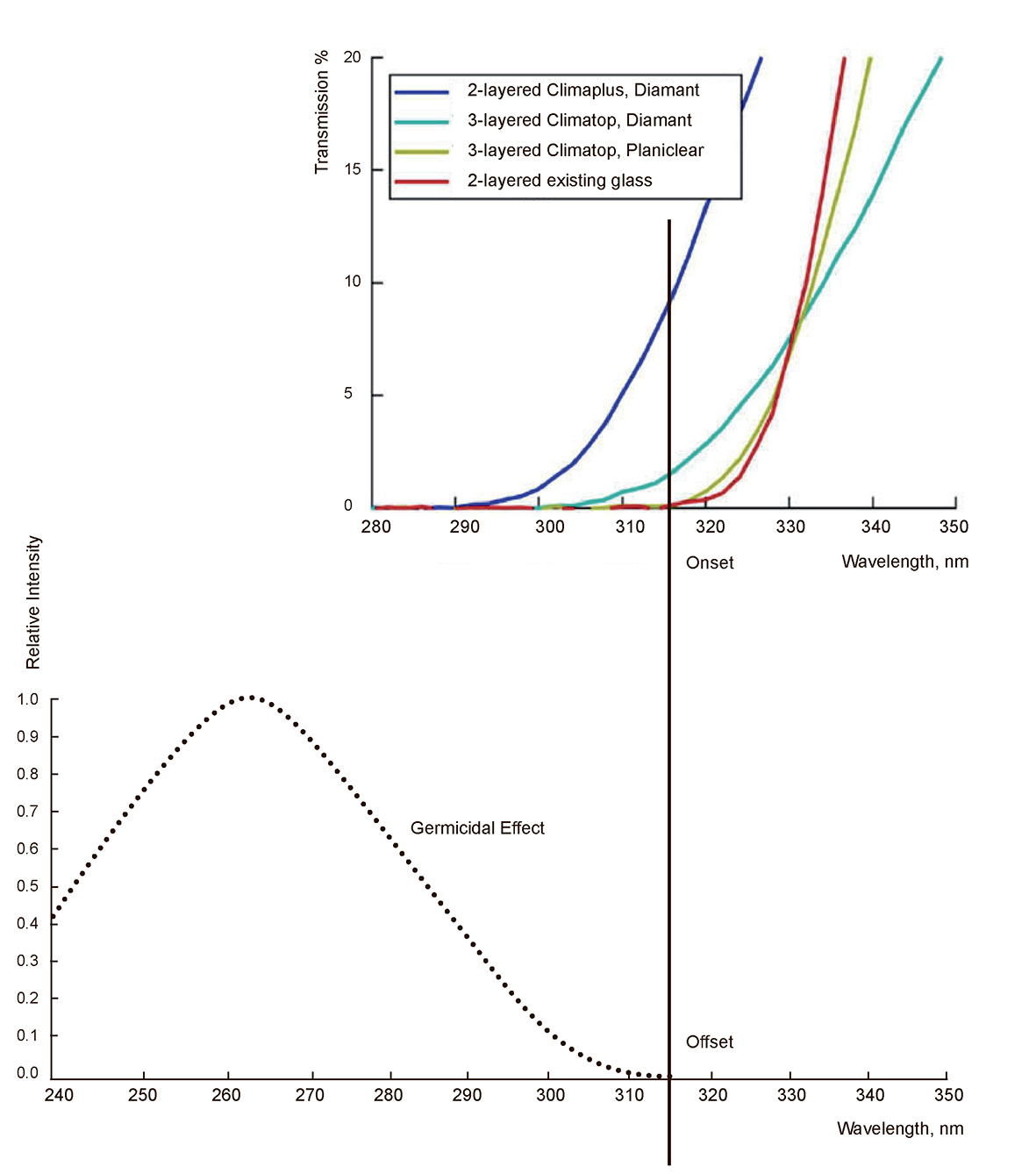

- The so-called “indoor generation” spends more than 90% of the time in the indoor environment. To implement solar protective, low energy windows, blocking out the short waved daylight from the indoor environment, seems problematic. Both when it comes to the fight against bacteria and virus – and the stimulating of the natural autoimmune system and the formation of vitamin D as a natural defense against infectious diseases and virus…

References

- Downes, A., Blunt, T. The Influence of Light upon the Development of Bacteria 1. Nature 16, 218 (1877).

- Nightingale F. Notes on nursing: What is and what is not. 1859. Based on F. Nightingales experiences e.g. from the Crimean War 1853-56.

- Howard E. Garden Cities of Tomorrow, reprinted 1902.

- BCG-vaccine Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, also called BCG vaccine is a vaccine against tuberculosis detected by the French bacteriologists Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin in 1921. The vaccine is mass-produced and later globally distributed from 1945. Source: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2013. Other vaccines, such as vaccines against diphtheria (1943) and neonathal tetanus (1949), are produced and marketed globally in the same period e.g. from Denmark. Source: K. Jensen. Bekæmpelse af infektionssygdomme, p 44 Nyt Nordisk Forlag Arnold Busck. 2002.

- Adams Annmarie. Medicine by Design: The Architect and the Modern Hospital, 1893–1943. University of Minnesota Press. 2008.

- Plowman R, Graves N, Griffin MA, Roberts JA, Swan AV, Cookson B, Taylor L. The rate and cost of hospital-acquired infections occurring in patients. Journal of Hospital Infections. PubMed, 2001.

- Hassan M, Tuckman H.P., Patrick R.H., Kountz D.S., Kohn J.L. Cost of hospital-acquired infection. National Institute of Health. PubMed, 2010.

- Prof. Kjeld Møller Pedersen, University of Southern Denmark, What you did not know about Denmark, DR2 d. 25.06.2013.

- Frimodt J, Ugeskrift for Læger 173/2, 01.10.2011: Over the years, Danish hospitals have regularly participated in national prevalence studies, which unfortunately – in relation to the increased attention in this area – has shown relatively constant frequencies of HI of 8-10 %.

- Dr. Chan Margaret, Director General, WHO. Maintaining momentum in an era of austerity, www.who.int 2011.

Can advancements in glass technology and architectural engineering help us strike a balance between energy conservation and access to germicidal UV light indoors?

Tel U