14 November 2023

The Cathedral – a heavenly measuring instrument

“With us it is Easter every day, except that Easter is celebrated once a year.” Martin Luther

Meridiana in San Petronio, Bologna by Gerd Folkers

Luigi Cornaro was worried. The camerlengo of Gregory XIII looked into the rapidly emptying coffers of Holy Mother Church. It was not that one had been starving, but the Turkish wars had been expensive. He himself had “donated” 70,000 scudi to the Holy League to become and remain cardinal chamberlain. The new threat, however, came from the wrong spirit, that of the Reformers or that of the scientists or, worse, from both. Thus Tycho Brahe, the famous Danish astronomer, built his new observatory on the island of Hven to explore the heavens. The Duke of Wolfenbüttel founded the Protestant University of Helmstedt to explore body and soul.

Cornaro had no illusions about the consequences. A reaction of the Mother Church was urgent, an image offensive that would be very expensive. The power of definition had to be regained: the power to enthrone saints, to set their holidays and to control daily peasant life along the “natural calendar”. The latter was based on the moon and did not fit so perfectly with the ecclesiastical calendar, which was, as usual for rulers, a solar calendar. It went back to Julius Caesar and was therefore called the “Julian” one. For its part, it did not quite coincide with the astronomical year.

The peasants didn’t care much, but the cardinals were upset that the vernal equinox no longer fell on March 21. This day had been set as the beginning of spring by the first Council of Nicaea in 325 because of this coincidence. On this date although the equinox fell further and further behind in the 365-day course of the year. Thus one lost the power to define on which day Easter Sunday fell, the most important day in the church year and the axiom of the holy church: the resurrection of Christ. In Nicaea, it had been established that Easter Sunday was the first Sunday after the first full moon in spring. In the second half of the 16th century, however, the equinox defining the beginning of spring took place ten days before the conventional date. Therefore, a new calendar had to be created to correct this deficiency. In order to attract experts who thought in the sense of the Mother Church, the Pope made an enticing offer. He built his own observatory in the Vatican Gardens, the “Tower of the Winds,” from which the present Vatican Observatory in Castel Gandolfo grew.

On the second floor is the Sala della Meridiana. The room is named after the meridian, which was inlaid in the floor with white marble in 1580. Through a hole in the fresco “Jesus Stills the Storm” on the south wall, the midday sun casts light on this meridian, which was used to measure the position of the sun at noon in each season and thus had a calendar correction function.

The idea of putting a point of the sun on a cathedral floor through a hole in the roof or wall at noon and thus establishing the meridian, the north-south line, is an old one. It is believed that as early as the 8th century, monastery churches sporadically experimented with sun position indicators when they had a medieval polymath for an abbot, such as in Salzburg with St. Virgil. Finally, in the Renaissance, the desire to experiment broke through and received (not entirely ideology-free) public support. The amount that the church put into astronomical research to maintain its power to define the date of Easter amounted to billions in today’s currency.

The Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna houses an early “modern” Meridiana. The basilica, built in 1390, has a north-south orientation almost parallel to the meridian. It is the largest brick church in the world and, according to plans by 1514 it should probably have been even larger. In Bolognese accounts, the present building is only a wing of the transept of the planned basilica. The finished building would have towered over St. Peter’s by far. Pope Pius IV forbade the expansion. Ignatio Danti created the Meridiana in 1575. The hole gnomon (1) in the church ceiling was only a few millimeters in size and drew a north-south line about 70 meters long on the church floor over the year, which is set in brass. At the highest point of the sun, the sunspot also provides the calendar date. The line is decorated with the zodiac lines, indicating how the sun passes through “the houses.” However, Danti made some compromises due to the existing architecture on the one hand, and politics and thus finances on the other. A five-member board of directors, the fabbriccieri, decided on the buildings at San Petronio. Danti had to squeeze his meridian line between the piers. The midday light spot touched the pedestals here and there and on some days was unusable. The insufficiently flat floor of the cathedral did the rest: Altogether, this resulted in a misalignment of 9° with respect to the true north-south axis. 75 years later, after Galileo had been involved and the Copernican conception of the world had slowly become established, the famous Cassini, in the course of further reconstructions in San Petronio, designed the meridian in the form we see it today.

However, the daily measurement also revealed the discrepancy between the ecclesiastical desired date of the beginning of spring on March 21 and the actual day-and-night line. The Julian calendar in force lagged by more than eleven minutes per year. In biblical dimensions, this quickly adds up to days. Thus, since the Council of Nicaea in 325, ten surplus days had already accumulated and tipped the calendar out of reality.

(1) Also pinhole, nodus, derived from sundials with shadow staff, Greek γνώμων (gnomon), shadow indicator. The pinhole is an inverse shadow indicator.

“The problem and at the same time the advantage of the sundial is that it shows the true time of the location.”

The Lutheran astronomer Tycho Brahe, whose writings were already on the index of the Spanish Inquisition, although he favored the geocentric worldview, hurt the Curia tremendously with his highly precise star measurements and contradiction to Aristotle, because it was in danger of losing support among the population because of its own inaccurate and bureaucratic calendars. Gregory XIII decided to take action in 1582, imposed the leap years and let the ten extra days since Nicaea simply disappear. The month of October was chosen as the time of disappearance, because its shortening caused the least amount of saints to lose their feast day. Ignatio Danti was a member of the papal commission.

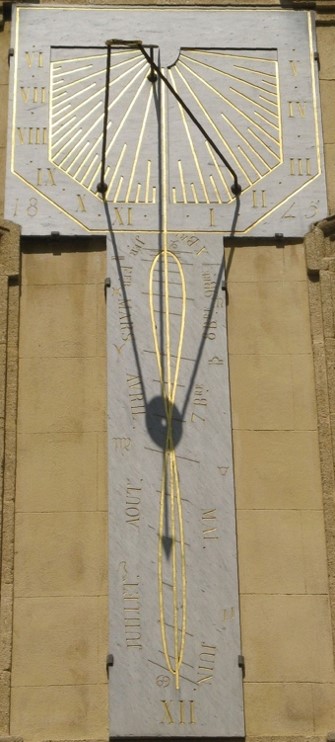

Only the western part of Christianity, especially the Catholic core countries, adopted the Gregorian calendar revolution. Protestants and Lutherans held on to the old calendar for a long time, Orthodox churches to this day, so that official, and in some cases legislative, intervention was necessary to calm the decades of calendar unrest. Some of the noon lines on church floors are surrounded by a strange loop in the shape of a recumbent but distorted figure eight. This figure eight shows the yearly progression of “true” time versus the “mean” time constructed by us humans. Since the earth rotates in an elliptical orbit around the sun, it does not always have the same distance and also not always the same speed relative to the sun. In addition, the axis around which our earth rotates once a day is inclined by 23.5° against the perpendicular to the orbit. From this it is easy to see that for every point on the earth a very own certain moment is “noon”, designated by the highest position of the sun. This makes appointments rather tedious. The time we use therefore assumes a fictitious earth, which describes a circular path and orbits the sun with its axis perpendicular. This is how the average time is created, which is also grouped into time zones around the earth from east to west, so that at least for a few hundred kilometers the time remains the same. The problem and at the same time the advantage of the sundial is that it shows the true time of the location.

If you build a sundial, you have to adjust its geometry to the exact location, at least to the latitude, so that the shadowing hand (gnomon) is parallel to the Earth’s axis. Of course, the Romans knew this. Their officials traveling to the north wore disc-shaped sundials of a few centimeters in diameter around their necks, the gnomons of which could be repositioned according to the latitudes.

The Basel train station of 1860 therefore had two clocks. The Swiss part of the station was based on Bernese time and noon, while the French part of the station was based on noon in Paris. Thus, southbound and northbound trains departing at the same time had twenty minutes difference with respect to a mean time.

The lying eight, an analemma, is the graphical solution of the time equation describing the difference between true and mean time.

This text was translated by Professor Gerd Folkers from the german version in his book “Faustmanns Hypsometer und andere seltsame Instrumente zur Vermessung der Welt” (2023)

Bónoli, Fabrizio: 1655-2005: 350 Years of the Great Meridian Line by G. D. Cassini in the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, http://stelle.bo.astro.it/ archivio/2005-anno-cassiniano/meridian_ing.htm.

Cassini, Giovanni Domenico: La meridiana del tempio di S. Petronio tirata, e preparata per le osseruazioni astronomiche l’anno 1665. Riuista, e restaurata l’anno 1695, Bologna: Vittorio Benacci, 1695, https://amshistorica. unibo.it/9, 15. 8. 2022.

Heilbron, John L.: The Sun in the Church. Cathedrals as Solar Observatories, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Luther, Martin: Summarien uber die Psalmen und Ursachen des Dolmetschens. Anno 1533, Heidelberg University Library, http://digi.ub.uni- heidelberg.de/diglit/luther1665/0011-0012, 13 Oct. 2016.

Manaugh, Geoff: Why Catholics Built Secret Astronomical Features Into Churches to Help Save Souls, 2016, www.atlasobscura.com/articles/catholics- built-secret-astronomical-features-into-churches-to-help-save-souls, 22. 8. 2022.

Tirapicos, Luís: On the censorship of Tycho Brahe’s books in Iberia, in: Annals of Science 77/1, 2020, pp. 96-107.

Comments