13 October 2025

A Little Ode to Light – From the Perspective of a Cultural Creator (or Culture Professional?)

Read the original German version of this contribution

Scientifically speaking, light is electromagnetic radiation within the visible spectrum. It appears both as a wave and a particle – and makes our perception of the world possible in the first place. Yet for us cultural creators, light is much more than a physical phenomenon: it is inspiration, mood-setter, and companion through life.

The Light of Provence

The first gentle light of morning warms my heart and soul – and my body too. For almost ten years now, I have spent half of each year in Provence, a region famous for its unique light. Not only because the sun shines here 300 days a year, but because the light, in interplay with the surroundings, has a singular brightness and colour: pale and delicate in the morning, richer at midday, and almost colourful, warm, and golden in the evening. This is likely also due to the Mistral, that often strong north wind blowing through the Rhône valley, quickly sweeping away clouds as they form.

This light has long attracted artists from all over the world – most notably the Impressionists such as Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Camille Pissarro. All of them tried to capture the special light of Provence. In the medieval town of Lacoste, a “colony” of Scandinavian artists emerged in the last century, which still exists today. Even now, light continues to draw artists to Lacoste. Among them is Peter Somm, the “painter of light” from Switzerland. Our foundation has been running a small art gallery for eight years. Each summer, we host an exhibition, both in the gallery and outdoors. The artworks shown are, in the broadest sense, connected to the wonderful surroundings, the place itself, and of course, the light. This year, we exhibited numerous works by Peter Somm.

Not only painters but also poets such as René Char and Albert Camus have been captivated by the light of Provence.

“Awakened by the sun flooding my bed. A day like a crystal cup overflowing with an uninterrupted blue and gold light.”

– Albert Camus

What Does Light Do to Us?

Light delights us, lifts our spirits, warms us in many ways, and accompanies us throughout the day. From morning to evening, light intensity, quality, and warmth change constantly. Light gently wakes us in the morning, grows intense and warm to hot by midday, and then softly closes the day. In Provence, the sunlight is so intense that we must protect ourselves from its radiation. The shadows into which we retreat make the light’s intensity and contrasts even greater, more striking, more intriguing. Light is fundamental to art. Where light meets an object, shadow forms behind it – creating depth, form, and spatiality. Shadows and light shape the landscape, the plants, the houses – they give them three-dimensionality. The Impressionists were fascinated by the constant change of light and colour. In this flux, one can also see symbolism – something divine. Concepts such as transience or threat, but also hope and confidence, are natural associations.

Different lighting moods throughout the day:

Light in Other Cultures

Art and culture are essential to humanity. During my roughly two years in Central and South America, I studied the historical buildings of the Aztecs, Mayas, Incas, and other cultures. Their richly decorated structures live through light and shadow. To us, the figures, symbols, and inscriptions may be difficult to interpret today, but for the people of that time they were messages from the spiritual realm, the world of their gods. Only the intense light made them readable carriers of these messages.

Light and Architecture

In architecture, daylight plays a decisive role – something already understood in antiquity. Imagine the Greek temples without the play of light and shadow: simply unthinkable. It is once again the plasticity created by light that gives architecture its vitality and continues to shape it today.

Daylight influences people’s well-being inside buildings. Sunlight provides warmth and solar energy, which we can use as a passive energy source. At the same time, architects must manage sunlight penetration and factor in the risk of overheating interiors. In recent decades, the world has grown warmer – there is no doubt about that. Balancing abundant light, effective use of solar energy, and avoiding overheating is one of our key challenges. At universities such as ETH Zurich, this topic has become well established. Yet in practice, much remains to be done – among developers, planners, and policymakers alike.

Two Practical Examples

At “Bob Gysin Partner Architekten”, we have, over the years, planned and realised many socially oriented buildings. We find the creation of housing for older people and workplaces for people with disabilities particularly rewarding architectural tasks.

Lanzeln Senior Centre, Stäfa

Our first residential and care centre was completed in 2010 and was honoured with the Age Award as the best senior centre in Switzerland. The site offered ideal conditions: a central location near the train station, with views of Lake Zurich to the south and vineyards to the north. We wanted everyone to benefit from this location. We designed an angled building with two equal-length wings, giving all rooms and main areas a southeast or southwest orientation – offering lake views without direct southern sun exposure. A terrace layer in front acts as a natural sunshade (brise-soleil), filtering the intense light while allowing outdoor use. This keeps the building cool in summer without complex technical systems.

Special attention was also given to communal areas: the light-filled entrance hall opens onto the landscape and lake. All key spaces – restaurant, dining room, library, fitness room, and hair salon – are connected to it. The publicly accessible, well-located restaurant attracts outside guests and creates a stimulating social meeting point for residents.

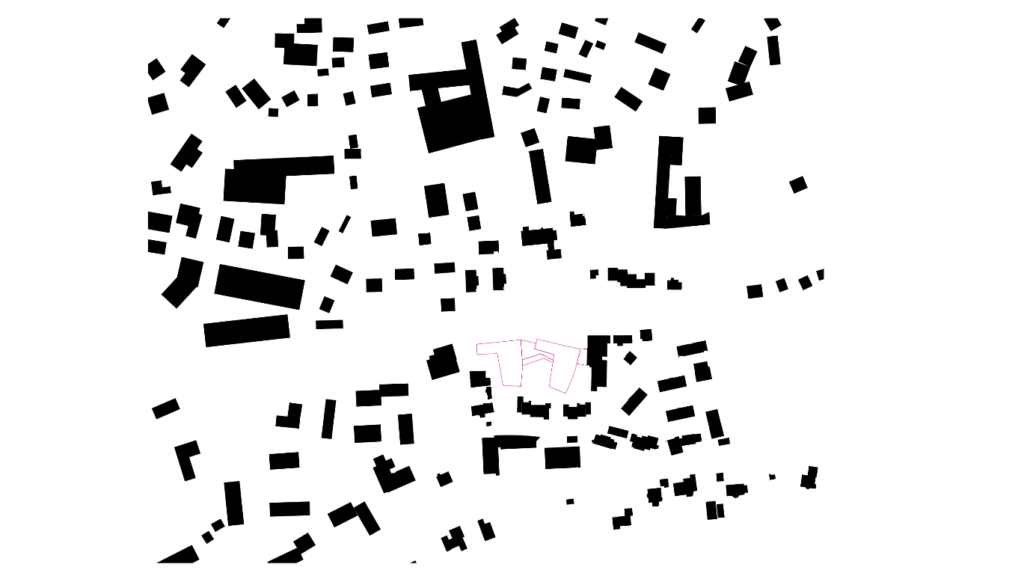

Day Centre Dielsdorf, 2012

Like the Stäfa project, this day centre originated from an architectural competition. The building provides a place where people with disabilities can engage in meaningful activities in a calm environment. The architecture here creates lighting conditions that are not only a high priority for people with disabilities – good visibility and an atmosphere of warmth and joy.

The project sits on a gently sloping western hillside. We designed an angled floor plan to achieve optimal daylight penetration. A central, wide, and elevated corridor with a “skylight band” connects the rooms, bringing daylight deep into the building and creating a bright, open core from which all spaces are accessed. Some communal rooms are open, others enclosed by lightweight walls with tall, glazed door elements. The deliberately colourful walls make the building cheerful and welcoming, creating light-filled spaces with a warm and lively atmosphere.

This house too demonstrates: sustainability does not arise from complex building technology, but from a clear architectural idea and intelligent light guidance. These are decisive for both the quality of the building and the well-being of its users. Sometimes less is more – restraint in technical and structural complexity pays off, even economically. Time and again, we have received compliments from caregivers and, above all, from the users themselves – the general sentiment being that they feel comfortable. The most beautiful reward for our work.

Conclusion

Whether in Provence, in ancient cultures, or in today’s architecture, light is more than brightness, more than a physical phenomenon. It is a source of life, a giver of mood, and a creative instrument. Architecture that uses light consciously is energy-efficient and creates atmosphere, orientation, and a sense of security.

«In einem der berühmtesten Zitate, die von ihm überliefert sind, äusserte sich der Kirchenvater Augustinus über die Zeit: «Was also ist die Zeit? Wenn mich niemand fragt, so weiss ich es; wenn ich aber jemandem auf seine Frage erklären möchte, so weiss ich es nicht. Das jedoch kann ich zuversichtlich sagen: Ich weiss, dass es keine vergangene Zeit gäbe, wenn nichts vorüberginge, keine zukünftige, wenn nichts da wäre …» Augustinus hätte in ähnlicher Form über das Licht sprechen können – und damit auch über das Dunkel oder über die Schatten. Aber er hat es nicht getan. Deshalb kann er uns mit dem Rätsel des Lichts nicht weiterhelfen, und wir müssen Wissen wie Zuversicht aus uns selbst schöpfen.» – Martin Heller aus Buch «Kompass des Lichts» (Scholz, Christian: Kompass des Lichts, Aesch, Schweiz: Edition Schwarzweiss, 2016)

Comments