29 April 2020

Coronavirus and Vitamin D: in the Sun and Air during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

During the 1918 influenza pandemic, some nurses fell ill, while others did not. Was it Vitamin D?

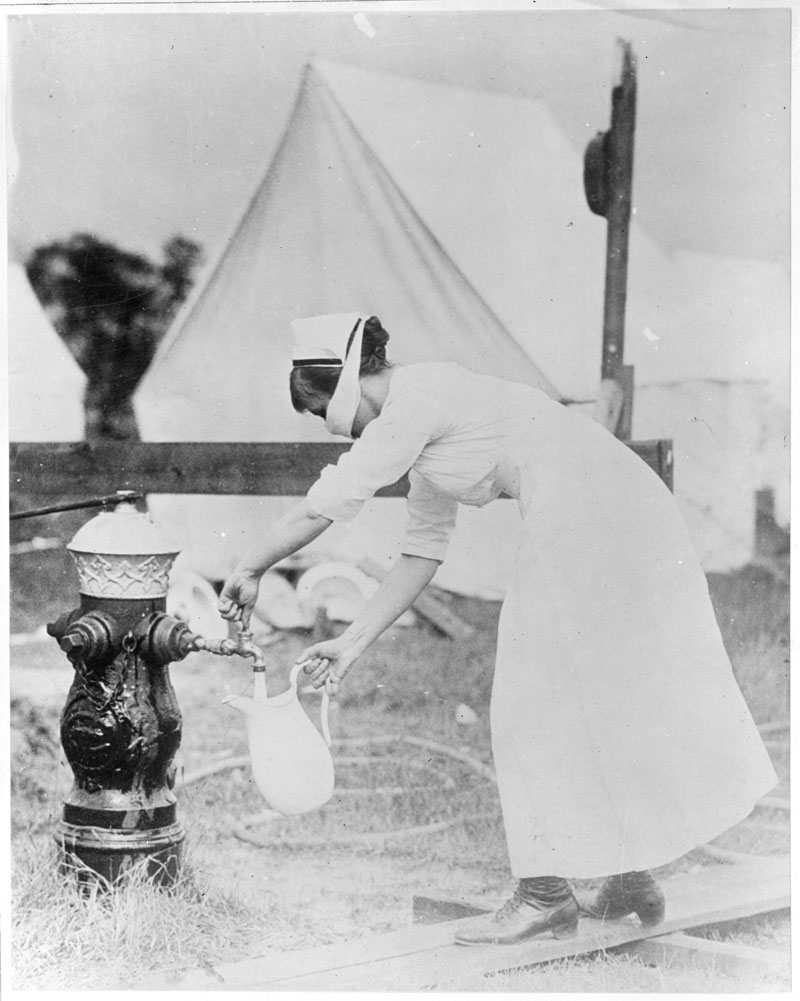

It is clear from recent reports that doctors and nurses in hospitals are at high risk of contracting Covid-19. A century ago, during the 1918 pandemic, medical staff were just as vulnerable to influenza. One of the biggest problems back then was a shortage of nurses. As they fell ill, patient care deteriorated, and hospitals began turning patients away. However, it was a different story at an emergency tented hospital set up in the United States to deal with the surge in seriously ill influenza patients. The open-air regimen used there seems to have protected front-line staff from infection.

“An invaluable incident to this treatment is the fact that in the open air, the immunity of the nurses and physicians is enormously increased, leaving them to carry out the great amount of work confronting them.”

The medical team at the Camp Brooks open-air hospital, in Boston, comprised 45 nurses and aids, 15 doctors, 20 sanitary corps men, and 74 orderlies. Apparently, just six nurses and two orderlies developed influenza. And in five of these cases exposure to the influenza virus may have taken place away from the hospital. If these figures are correct, people were much safer working there than elsewhere at the time. [1,2]

Camp Brooks opened on September 9, 1918 and closed a month later. During this period, 351 seriously ill patients received treatment. Of these, 36 died. According to William Brooks, who was the Surgeon General of the Massachusetts State Guard, conditions in other hospitals were not as good. One of them took in 70 influenza patients and, within three days, one quarter of them were dead. Also 17 nurses fell ill. [3]

Brooks stated the reason patients did not do well in ordinary hospitals was because they needed `the maximum’ of fresh air to recover. In his opinion, such hospitals could not provide them with this — no matter how well ventilated. He also stated influenza patients needed to be in direct sunlight all day, which they could not in an ordinary hospital.

Disinfection and Ventilation

One thing that William Brooks and his team insisted on was that influenza patients got fresh air at all times — during the day and at night. At the time, health officials and doctors believed that influenza and many other infections were transmitted through the air. They thought fresh air and sunlight stopped them from spreading. Also, according to health experts of the period, breathing pure air reduced the risk of re-infection and cross-infection and helped patients get well. These were not new ideas. Florence Nightingale wrote about them in the late 1850s. During the late 1960s, scientists found that fresh outdoor air can indeed kill bacteria and viruses — and that it does so during the day and at night.

Back in 1918, these disinfecting properties could have been what Surgeon General Brooks was alluding to when he wrote about fresh air. After all, he did insist on the maximum of ventilation at night, as well as during the daytime. If so, the key to the apparent success of open-air hospitals could be that they provided an aseptic, or surgically sterile environment, around-the-clock. This would have minimised the viral load to which nurses and patients were exposed. Perhaps this is why fewer nurses caught influenza. And again, during the daytime, they and their patients were in the sun when it was out. The sun’s ultraviolet radiation is known to be the most important natural inactivator of viruses. [4] There is good evidence that it kills the influenza virus. [5]

Or Was it Vitamin D?

Another benefit of sun exposure is that it helps maintain healthy vitamin D levels. Today, nurses and other hospital staff spend long hours working indoors and are at risk of vitamin D deficiency. [6] Low vitamin D levels may put them at risk of a range of health problems — including respiratory infections. The same is true of other vulnerable groups such as the elderly and housebound. In the current coronavirus pandemic vitamin D, or rather a deficiency of it, could be very important indeed. There is growing support for this idea among researchers. [7,8,9]

Vitamin D may have made a difference in the 1918 pandemic. But vitamin D was not discovered until later. So doctors didn’t know about it, or its benefits. Equally, no one knew what pathogen they were dealing with back in 1918. Some of the symptoms were so severe doctors were not sure it was influenza. [10]

All Three?

Coming up to date, it is not yet certain that sunlight kills the coronavirus. But it would be surprising if it did not. Equally, we can’t be sure that the fresh outdoor air kills it. But given the sensitivity of other viruses to its germicidal effects — the Open Air Factor— it seems likely that it does. [11] Vitamin D might help in overcoming the virus too, although we don’t know that yet either. No results of any clinical trials have been published.

Medical thinking has changed a lot since the 1918 influenza pandemic. Maybe they could help other vulnerable people too, as long as they take care in the sun. Of course, social distancing policy must still be observed — and hands must be washed.

Originally published at medium.com.

References

- Weapons against influenza. Am J Public Health 1918 Oct;8(10):787–8.

- Influenza at the Camp Brooks Open Air Hospital. JAMA. 1918;71:1746–1747.

- Brooks WA. The open air treatment of influenza. Am J Public Health. 1918;8:746–750.

- Lytle CD, Sagripanti JL. Predicted inactivation of viruses of relevance to biodefense by solar radiation. J Virol. 2005 Nov;79(22):14244–52.

- Schuit M, Gardner S, Wood S et al. The influence of simulated sunlight on the inactivation of influenza virus in aerosols. J Infect Dis 2020 Jan 14;221(3):372–378.

- Sowah D, Fan X, Dennett L, Hagtvedt R, Straube S. Vitamin D levels and deficiency with different occupations: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017;17:519.

- Laird E, Kenny RA. Vitamin D deficiency in Ireland — implications for COVID-19. Results from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Dublin: Trinity College Dublin, April 2020. https://tilda.tcd.ie/publications/reports/pdf/Report_Covid19VitaminD.pdf

- Grant WB, Lahore H, McDonnell SL, Baggerly CA, French CB, Aliano JL and Bhattoa HP. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients 2020 Apr 2;12(4). pii: E988. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32252338

- Cartney D, Byrne D. Optimisation of vitamin D status for enhanced immuno-protection against Covid-19. Ir Med J 2020;113(4):58.

- Hobday RA. The open-air factor and infection control. J Hosp Infect 2019;103:e23-e24. 1016/j.jhin.2019.04.003

- Hobday RA and Cason JW. The open-air treatment of PANDEMIC INFLUENZA. Am J Public Health 2009;99 Suppl 2:S236–42. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2008.134627

Hello Richard! Would it be possible to carry out a regression analysis where the dependent parameter is the % of people infected in the country and the independent parameters are: 1. How much the population stays outdoors expressed in %. 2. The average temperature of the country. 3. Number of inhabitants per square meters. 4. How long time has the country has been shut down? To me, it seems that countries with high temparatures and a lot of sunlight are milder hit by the Covid-19. The regression analysis would tell us which one of the independent parameters that has the highest impact on the % of infected people.

Hello Asger. It would be an interesting study and probably a very valuable one. I’m looking at what’s being published on vitamin D deficiency at the moment. There is a new study on the latitude gradient of Covid-19 by researchers at Liverpool University that looks promising;

https://news.liverpool.ac.uk/2020/04/21/covid-19-vitamin-d-and-latitude/

Another study you may be interested in is Seasonality and uncertainty in COVID-19 growth rates. by Merow and Urban medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.19.20071951.

With best regards,

Richard

Thank you very much, Richard. Take care!

Considering the potential benefits of fresh air and sunlight in combating respiratory infections, should hospitals prioritize designs that optimize natural ventilation and exposure to sunlight?

Tel U