7 November 2025

SUN 1913

‘Technische Träume’ (‘Technical Dreams’) is the title of a book from 1922 that we received as a gift from a scientist during a fellowship at the Paul Scherrer Institute. The cover shows a solar power station in a suburb of Cairo, which was built by American inventor Frank Shuman in 1913.

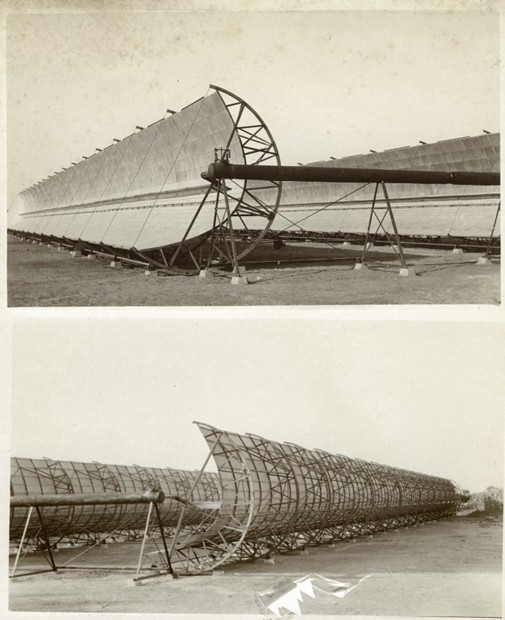

The station enabled Shuman and his British financiers to demonstrate that solar energy was cheaper than the alternative commonly used at the time, coal from England. The station consisted of five rows of parabolic mirrors, each 62 metres long and four metres wide. The troughs automatically aligned themselves with the position of the sun. The associated steam engine, which was specially developed for this application, had an output of 55 hp and could pump 2,000 litres of water per minute from the Nile to irrigate cotton fields.

The tragedy of the story? In 1908, oil was discovered in what is now Iran – after British investors had already abandoned the search for financial reasons. In 1914, the First World War broke out. The station was dismantled and the operators returned to their home countries.

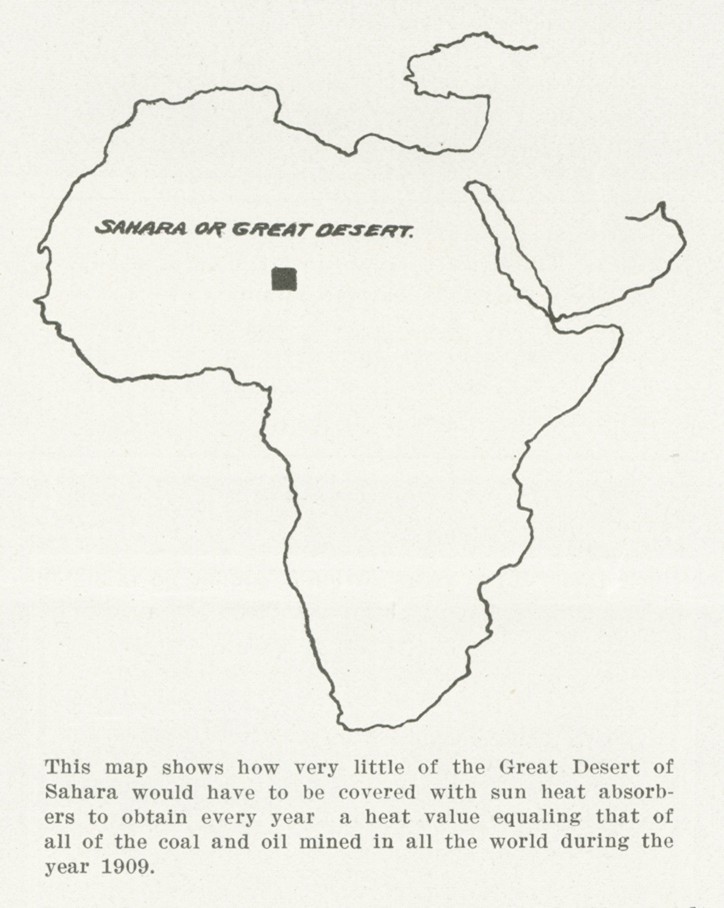

After the nomination by the Federal Office of Culture to represent Switzerland at the Cairo Biennale, we researched the exact location of the former solar power station with the help of a local historian, reconstructed a segment of the solar concentrator and wrote a short story with Egyptian author Wageh George about the construction and inauguration of the avant-garde solar power station [1]. This story, which was available to take away during the exhibition in the form of a Reclam-style booklet, contains an illustration that Frank Shuman published in Scientific American in 1914. The picture shows the African continent with a small square in the Sahara corresponding to the area that would have been needed at that time to supply humanity with solar energy. Similar illustrations were published again in 2009 by the Desertec Foundation, co-financed by the Club of Rome [2]. Although the square covers a larger part of the Sahara, it is still relatively small.

We often ask ourselves ‘what if?’ Where would we be if oil had been discovered later or not at all in the Middle East? Could solar energy have become established, at least near the equator? Would solar colonialism have emerged?

What if we were to invest a lot of money in solar energy and the electrification of our society today? Knowing that investments in the transformation will lead to savings in the future, that reducing air pollutants will enable a healthier life, and that relations with oil-rich countries will ease. Solar energy is now cheaper than electricity from fossil fuels. A win-win-win situation?

The picture is more complex. For many people, the investments will come too late. Even if we stopped CO2 emissions immediately, sea levels would rise several metres over the next few centuries, displacing millions of people. Nevertheless, we must do everything humanly possible to accelerate the technical and cultural metamorphosis. The crucial question is how quickly and civilised we can transform ourselves. Frank Shuman wrote in 1914: ‘One thing I feel sure of, and that is that the human race must finally utilize direct sun power or revert to barbarism.’

About Hemauer/Keller

Hemauer/Keller use a wide range of artistic media and practices in their art, ranging from photography and video to installations and performances. Many of their works reflect on the important role that fossil fuels play in everyday life, geopolitics and culture. In 2006, they heralded the era of “post-petrolism” with a manifesto and a performance at the Kunsthof Zurich. They examine forgotten innovations, missed opportunities and unused alternatives in particular, such as in the multi-part work ‘No1 Sun Engine’ about the world\’s first thermal solar power plant, which was developed by American engineer and inventor Frank Shuman in Egypt in 1913 and realised by Hemauer/Keller for the International Art Biennale in Cairo in 2008. Their documentary essay ‘A Road Not Taken’ (2010) deals with the solar system that President Jimmy Carter installed on the roof of the West Wing of the White House, which was dismantled seven years later during Ronald Reagan\’s presidency. Hemauer/Keller’s works are based on research and inspired by close collaboration with scientists from the humanities and natural sciences. In most of their works, this documentary and scientific aspect is seamlessly combined with poetic images and practices, often with a humorous twist.

Comments